In 1924, Robert Frank was born in Zurich, Switzerland to the daughter of a wealthy factory owner and a successful businessman who was also an amateur photographer. After graduating from high school, he began an apprenticeship in 1941 with Hermann Segesser, a photographer and retoucher who lived in the same apartment building as Frank’s family. The next year, he began to work for the Zurich commercial photographer Michael Wolgensinger who introduced him to Switzerland’s active magazine, newspaper, and book publishing industry. At the end of his extensive training, Frank made 40 Fotos, a hand-bound volume of photographs that shows the eclectic influences he had absorbed during his early years.

Frustrated by the constraints of his homeland, Frank left Switzerland in 1947 and immigrated to the United States and was hired by Harper’s Bazaar in New York. Bored with his new job, he quit later that year and traveled to South America, roaming extensively throughout Peru. Using both his 2¼ inch camera as well as a newly acquired 35mm Leica camera, he photographed Peru’s people, rather than its monuments and mountains; as he later said, he preferred the present and “things that move.” In early 1949, after returning to New York, he made another hand-bound book of his photographs. In 1950, he participated in the group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art. He also married fellow artist, Mary Lockspeiser.

Though he was initially optimistic about the United States, Frank’s perspective quickly changed as he confronted the fast pace of American life and what he saw as an overemphasis on money. He now saw America as an often bleak and lonely place, a perspective that became evident in his later photography. He continued to travel, moving his family briefly to Paris. In 1953, he returned to New York and continued to work as a freelance photojournalist for McCall’s, Vogue, and Fortune.

From 1949 to 1953 Frank wandered restlessly, traveling back and forth between New York and Europe. In each place, he focused on one or two subjects that expressed his understanding of the people and their culture. In order to create a stronger impact and address larger ideas, he also endeavored to make sequences of his photographs that he hoped would be published in Life or other magazines. However, although he was hailed as “a poet with a camera,” his photographic sequences were rarely published. With few commercial outlets for his series, Frank continued to make hand-bound books of photographs, including Mary’s Book, an album of 72 photographs and writings he made for his wife, and Black White and Things, his most accomplished sequence to date.

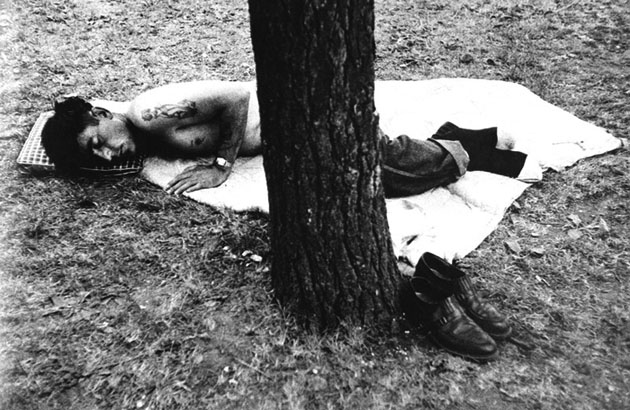

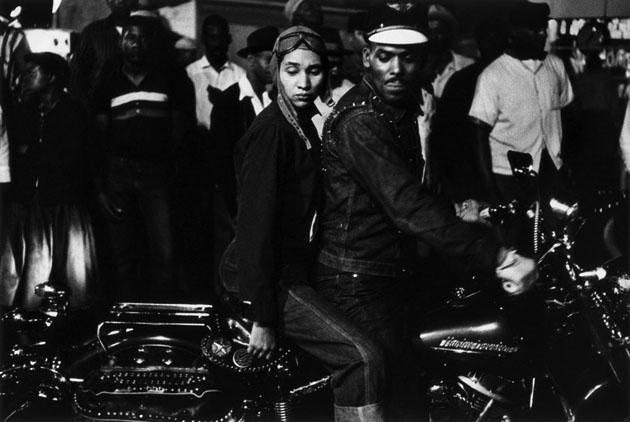

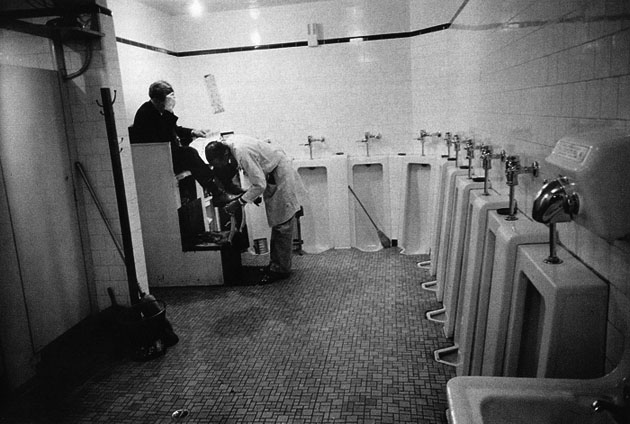

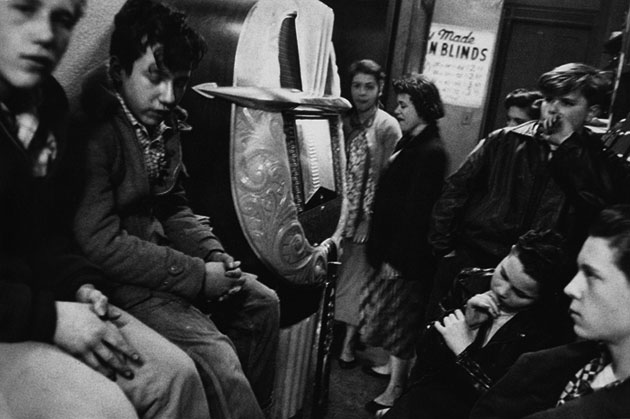

When Frank returned to New York in 1953, he was frustrated that his photographs had not been more widely published. In the fall of 1954, he applied to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for a fellowship “to photograph freely throughout the United States.” He was awarded a fellowship in the spring of 1955 and began to make the photographs that would comprise The Americans. After buying a used Ford, Frank made a few short trips that summer before embarking on a nine-month journey that would cover 10,000 miles and extend across the United States. With no set itinerary, he drove sometimes alone and sometimes with Mary and their two children, Pablo and Andrea. In each place he stopped, he tried to get a sense for the flavor of peoples’ lives by visiting ordinary places—the local Woolworth’s, coffee shops, cemeteries, parks, banks, hotels, and post offices, as well as train and bus stations all provided him with opportunities to observe a range of Americans without drawing too much attention to himself.

After making a few more trips in the summer of 1956, Frank spent almost a year making his book. First, he developed the 767 rolls of film he had shot for the project and made contact sheets of them. Then he reviewed the more than 27,000 frames and made more than a thousand rough 8 by 10 inch work prints of the images that intrigued him. After refining the selection, he sequenced the photographs and asked Jack Kerouac to write an introduction to the book. When The Americans was published, first in France in 1958 and then in the United States in 1959, it was unlike almost any other photography book ever produced. In 83 provocative but frequently poignant photographs, Frank looked beneath the surface of American life to reveal a people often plagued by racism, ill-served by their politicians, and rendered numb by a rapidly rising culture of consumption. Yet he also found new areas of beauty in overlooked corners of American life and in the process helped redefine the icons of America. In his photographs of diners, cars, and even the road itself, Frank pioneered a seemingly intuitive, immediate, off-kilter style that was as innovative as his subjects. So too was the way he tightly bound his photographs, linking them thematically, conceptually, formally, and linguistically to present a haunting picture of mid-century America. As Kerouac wrote in his introduction: “The humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures!”