| |

Published: March 19, 2006

IN

1999 Philip-Lorca diCorcia set up his camera on a tripod in Times

Square, attached strobe lights to scaffolding across the street

and, in the time-honored tradition of street photography, took

a random series of pictures of strangers passing under his lights.

The project continued for two years, culminating in an exhibition

of photographs called "Heads" at Pace/MacGill Gallery in Chelsea.

"Mr. diCorcia's pictures remind us, among other things, that we

are each our own little universe of secrets, and vulnerable,"

Michael Kimmelman wrote, reviewing the show in The New York Times.

"Good art makes you see the world differently, at least for a

while, and after seeing Mr. diCorcia's new 'Heads,' for the next

few hours you won't pass another person on the street in the same

absent way." But not everyone was impressed.

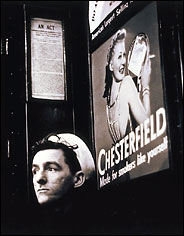

Pace/MacGill

Gallery, New York

The man in "Head No. 13, 2000," by Philip-Lorca diCorcia

is Erno Nussenzweig. When he saw his picture in an exhibition

catalog for diCorcia's "Heads," he sued the photographer

and his gallery.

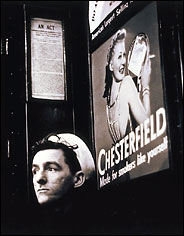

Metropolitan

Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive

Walker Evans took a series of pictures on the sly in the

subway in the 1940's; "Subway Passenger, New York City."

When

Erno Nussenzweig, an Orthodox Jew and retired diamond merchant

from Union City, N.J., saw his picture last year in the exhibition

catalog, he called his lawyer. And then he sued Mr. diCorcia

and Pace for exhibiting and publishing the portrait without

permission and profiting from it financially. The suit sought

an injunction to halt sales and publication of the photograph,

as well as $500,000 in compensatory damages and $1.5 million

in punitive damages.

The

suit was dismissed last month by a New York State Supreme

Court judge who said that the photographer's right to artistic

expression trumped the subject's privacy rights. But to many

artists, the fact that the case went so far is significant.

The

practice of street photography has a long tradition in the

United States, with documentary and artistic strains, in big

cities and small towns. Photographers usually must obtain

permission to photograph on private property — including

restaurants and hotel lobbies — but the freedom to photograph

in public has long been taken for granted. And it has had

a profound impact on the history of the medium. Without it,

Lee Friedlander would not have roamed the streets of New York

photographing strangers, and Walker Evans would never have

produced his series of subway portraits in the 1940's.

Remarkably,

this was the first case to directly challenge that right.

Had it succeeded, "Subway Passenger, New York City," 1941,

along with a vast number of other famous images taken on the

sly, might no longer be able to be published or sold.

In

his lawsuit, Mr. Nussenzweig argued that use of the photograph

interfered with his constitutional right to practice his religion,

which prohibits the use of graven images.

New

York state right-to-privacy laws prohibit the unauthorized

use of a person's likeness for commercial purposes, that is,

for advertising or purposes of trade. But they do not apply

if the likeness is considered art. So Mr. diCorcia's lawyer,

Lawrence Barth, of Munger, Tolles & Olson in Los Angeles,

focused on the context in which the photograph appeared. "What

was at issue in this case was a type of use that hadn't been

tested against First Amendment principles before — exhibition

in a gallery; sale of limited edition prints; and publication

in an artist's monograph," he said in an e-mail message. "We

tried to sensitize the court to the broad sweep of important

and now famous expression that would be chilled over the past

century under the rule urged by Nussenzweig." Among others,

he mentioned Alfred Eisenstaedt's famous image of a sailor

kissing a nurse in Times Square on V-J Day in 1945, when Allied

forces announced the surrender of Japan.

Several previous cases were also cited in Mr. diCorcia's defense.

In Hoepker v. Kruger (2002), a woman who had been photographed

by Thomas Hoepker, a German photographer, sued Barbara Kruger

for using the picture in a piece called "It's a Small World

... Unless You Have to Clean It." A New York federal court

judge ruled in Ms. Kruger's favor, holding that, under state

law and the First Amendment, the woman's image was not used

for purposes of trade, but rather in a work of art.

Also

cited was a 1982 ruling in which the New York Court of Appeals

sided with The New York Times in a suit brought by Clarence

Arrington, whose photograph, taken without his knowledge while

he was walking in the Wall Street area, appeared on the cover

of The New York Times Magazine in 1978 to illustrate an article

titled "The Black Middle Class: Making It." Mr. Arrington

said the picture was published without his consent to represent

a story he didn't agree with. The New York Court of Appeals

held that The Times's First Amendment rights trumped Mr. Arrington's

privacy rights.

In

an affidavit submitted to the court on Mr. diCorcia's behalf,

Peter Galassi, chief curator of photography at the Museum

of Modern Art, said Mr. diCorcia's "Heads" fit into a tradition

of street photography well defined by artists ranging from

Alfred Stieglitz and Henri Cartier-Bresson to Robert Frank

and Garry Winogrand. "If the law were to forbid artists to

exhibit and sell photographs made in public places without

the consent of all who might appear in those photographs,"

Mr. Galassi wrote, "then artistic expression in the field

of photography would suffer drastically. If such a ban were

projected retroactively, it would rob the public of one of

the most valuable traditions of our cultural inheritance."

Neale

M. Albert, of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison,

who represented Pace/MacGill, said the case surprised

him: "I have always believed that the so-called street

photographers do not need releases for art purposes. In

over 30 years of representing photographers, this is the

first time a person has raised a complaint against one

of my clients by reason of such a photograph."

State

Supreme Court Justice Judith J. Gische rejected Mr. Nussenzweig's

claim that his privacy had been violated, ruling on First

Amendment grounds that the possibility of such a photograph

is simply the price every person must be prepared to pay

for a society in which information and opinion freely

flow. And she wrote in her decision that the photograph

was indeed a work of art. "Defendant diCorcia has demonstrated

his general reputation as a photographic artist in the

international artistic community," she wrote.

But

she indirectly suggested that other cases might be more

challenging. "Even while recognizing art as exempted from

the reach of New York's privacy laws, the problem of sorting

out what may or may not legally be art remains a difficult

one," she wrote. As for the religious claims, she said:

"Clearly, plaintiff finds the use of the photograph bearing

his likeness deeply and spiritually offensive. While sensitive

to plaintiff's distress, it is not redressable in the

courts of civil law."

Mr.

diCorcia, whose book of photographs "Storybook Life" was

published in 2004, said that in setting up his camera

in Times Square in 1999: "I never really questioned the

legality of what I was doing. I had been told by numerous

editors I had worked for that it was legal. There is no

way the images could have been made with the knowledge

and cooperation of the subjects. The mutual exclusivity

that conflict or tension, is part of what gives the work

whatever quality it has."

Mr.

Nussenzweig is appealing. Last month his lawyer Jay Goldberg

told The New York Law Journal that his client "has lost

control over his own image."

"It's

a terrible invasion to me," Mr. Goldberg said. "The last

thing a person has is his own dignity."

Photography

professionals are watching — and claiming equally

high moral stakes. Should the case proceed, said Howard

Greenber

|

|

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive