Shooting Black-and-White Film in Medium Format

Today’s

digital cameras are capable of awesome imaging

performance and they offer an unparalleled

combination of convenience, efficiency,

and cost effectiveness that has made them

the dominant mode of image capture. Nevertheless,

shooting black-and-white film, especially

in medium format, is a fascinating and worthwhile

experience that’s rewarding, fun, and

can also go a long way toward making you

a more thoughtful and effective digital

photographer.

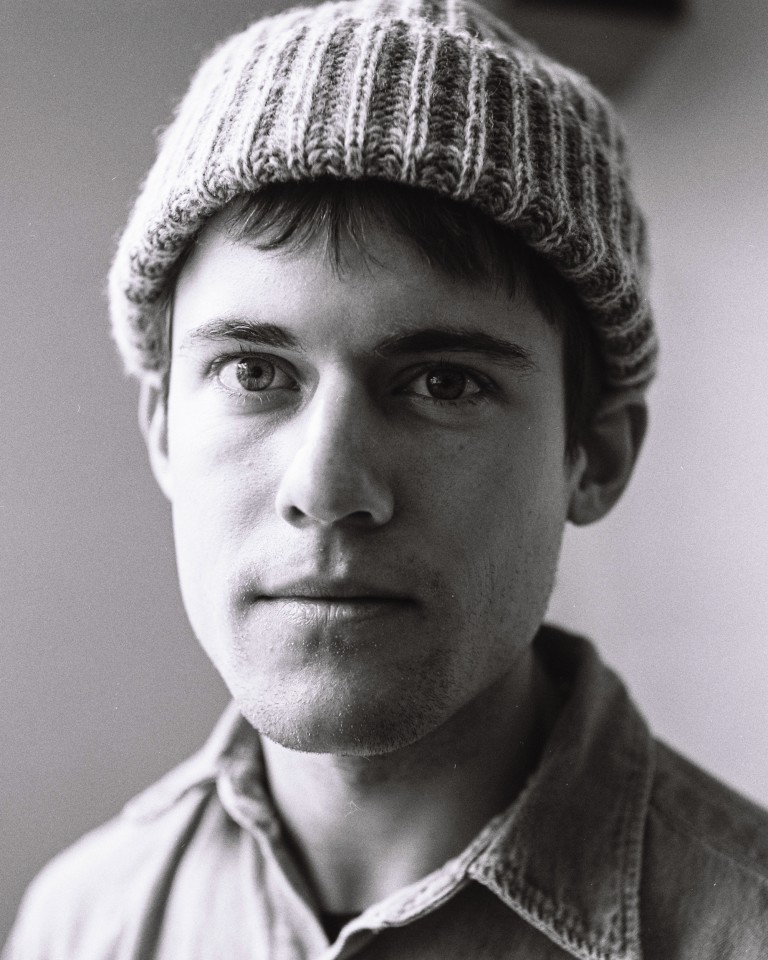

Nathan

the Barista: Rolleiflex 3.5E with 75 f/3.5

Zeiss Planar lens and Rolleinar #1 Series

2 close-up lens;

1/60-second at f/5.6; handheld on Kodak

Tri-X Professional

Loading

a roll of 120 film into, say, an old Rolleiflex

twin-lens reflex may seem like a quaint

and tedious procedure compared to inserting

a memory card into your DSLR. Using an exposure

meter, setting the aperture and shutter

speed individually, and focusing manually

certainly takes more time and effort than

using your camera’s built-in auto-exposure

and autofocus systems. And having to wait

for the film to be developed before you

can see the results will certainly test

the patience of those accustomed to assessing

their captured images immediately on the

LCD. However, this “retro” experience

forces you to slow down, take a deliberate

approach, and it gives you that inimitable

feeling that you’re creating something

for the ages. Perhaps that’s why so many

art photographers and creative shooters

continue to shoot at least some of their

work on film, and to favor the traditional

black-and-white medium.

The

image capture system you use does

make a difference!

Yes,

as the saying goes, it’s the person behind

the camera who determines the quality, originality,

and significance of virtually any photograph.

But photography is also a technologically

based art form, and that’s why the type

of equipment and capture medium you use

to create images also has a direct influence

on the final results. If you examine the

pictures on these pages, which I shot on

Kodak Professional Tri-X 120 roll film with

50- to 60-year-old manual exposure twin

lens reflexes (TLRs), they look qualitatively

and emotionally different from what you’d

typically shoot with a modern DSLR. They

have a kind of quiet, contemplative grandeur

that results from the slow, deliberate approach

you must use with this kind of camera and

the limitations it imposes on the photographer.

And the limited depth of field you get when

shooting medium format at large apertures

throws the background and foreground pleasantly

out of focus.

Nathaniel

and Colette: Rolleiflex Automat MX with

75mm f/3.5 Zeiss Tessar lens and Rolleinar

#1 close-up lens;

1/25-second at f/4; handheld on Kodak Tri-X

Professional

With

the exception of the Mamiya C220, all the

cameras I used lack interchangeable lenses

and only focus down to about three feet

(which is why I used Rolleinar close-up

lenses to get closer to the subject, in

some cases). The fact that the viewing image

with a waist-level-viewing TLR is reversed

left to right makes it challenging to follow

action, but it also encourages careful framing

and composition, which is a big plus for

portraiture. And, of course, you’re limited

to 12 exposures per roll, costing roughly

50 cents apiece (not including developing,

scanning, and printing), which really motivates

you to make each one count.

Finally,

using an exposure meter to calculate and

set the exposure encourages you to really

think about the effects of apertures and

shutter speeds on the final image, and to

carefully consider whether you’re exposing

for the highlights, shadows, and mid-tones.

In short, shooting film in a classic TLR

or roll film folding camera forces you to

take a slow, disciplined approach that is

all too often lacking in today’s fast-paced

digital photography, where most users fall

back on their camera’s automation and

the essentially unlimited image-capture

capability of a high-speed, high-capacity

memory card.

Portrait

of The Artist: Rolleiflex Automat MX with

75mm f/3.5 Schneider Xenar lens and Rolleinar

#1 close-up lens;

1/50 sec at f/5.6; handheld on Kodak Tri-X

Professional

What

you’ll need to get started

If

you already own or have access to a well-functioning,

medium-format roll film camera, all you

really need to acquire is: 120 roll film

(I recommend Kodak

Tri-X or Ilford

FP4 Plus) and an accurate, working exposure

meter. The current Sekonic

L-208 Twin Mate meter is a good choice,

or you can go for a classic used meter such

as the Gossen Luna-Pro. Make sure the meter

you choose is a modern battery-powered type;

older selenium meters are OK, but they generally

aren't sensitive enough to read in extremely

low light.

Sekonic

L-208 Twin Mate Light Meter

If

you’re not familiar with shooting roll

film, it’s best to shoot at least 100

exposures to get comfortable and creative

with this medium, and 10 rolls will allow

you to shoot 120 images in the 2-1/4 x 2-1/4-inch

format. If you take your time, this will

be sufficient to give you a new mindset

and perspective that are virtually guaranteed

to enhance your digital shooting capability.

If you don’t have a medium-format camera

available, you can find a good used one

at relatively modest cost in the B&H

Used Department.

Choosing

a medium-format camera

Medium-format

cameras come in a wide variety of types,

including TLRs, SLRs, solid-bodied press

cameras, and scale focusing and rangefinder

folding cameras in formats ranging from

6 x 4.5cm to 6 x 9cm, and even some panoramic

options going up to 6 x 17cm. Since the

only remaining roll film size that’s widely

available is the paper-backed 120 (220 is

still sold in a limited range) make sure

the camera you pick takes that size film.

There

is certainly nothing wrong with using a

medium-format-film SLR, such as a Hasselblad

500 C/M, Mamiya RB67 or 645, Pentax 6x7

or 645, etc., but for this project I decided

to concentrate on TLRs. They’re simple,

durable designs with quiet, low-vibration

leaf shutters and the fact that they don't

have a flipping mirror allows you to shoot

sharp handheld pictures at slower shutter

speeds. Here are some recommendations:

Rolleiflex:

These timeless classics are the standard

by which other TLRs are judged and they

still command premium prices. However, they

do provide automatic first frame positioning

(no red window or first frame positioning

marks to line up) and automatic parallax

compensation. If you’re on a budget, go

for the Rolleiflex Automat MX of the early

to mid ’50s with a fine, quality coated

Zeiss Tessar 75mm f/3.5 or Schneider Xenar

75mm f/3.5 lens. Late model Rolleis like

the 3.5 F and 2.8 F with Zeiss Planar or

Schneider Xenotar lenses are the cream of

the crop, but they generally sell for a

bit more, depending on condition.

Rolleiflex

3.5E: Perhaps the most affordable, relatively

late model high-end Rolleiflex, it has the

superb

75mm f/3.5 Planar lens and, like all

Rolleiflexes since 1937, it provides automatic

first-frame positioning and

auto-parallax compensation over the entire

focusing range.

Rolleicord:

These little brothers of the Rolleiflex

are simpler in design but do also provide

auto parallax compensation and accept Rolleinar

close-up lenses. Make sure to get one with

a Schneider Xenar 75mm f/3.5 lens and Synchro-Compur

shutter. The most desirable ones are the

late model Va and Vb, the latter with interchangeable

viewing screens. However, older models such

as the III and IV are still very competent

picture takers.

Mamiya

and Mamiyaflex: These rugged, high-quality

machines are the only truly successful interchangeable-lens

TLRs and they hold up very well. Lens sets

from 55mm to 250mm are available, but both

the standard Mamiya-Sekor 80mm f/2.8 and

105mm f/3.5 lenses are of excellent quality.

Older models, such as the Mamiyaflex C2,

Mamiya C22, and C3 are less costly, and

later models such as the C220 and C330 are

more expensive. They’re larger and heavier

than Rolleis, and they focus much closer

without requiring close-up lenses, but they

have no parallax compensation other than

lines on the focusing screen to guide your

framing.

Mamiya

C220: Larger and heavier than the Rolleiflex,

this robust interchangeable-lens TLR can

focus much closer

without accessories, but you have to manually correct

for parallax at close shooting distances.

The standard 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor lens

is outstanding, and lenses from 50-250mm

are available.

Zeiss

Ikon Ikoflex: They’re great cameras,

in terms of optics and focusing-screen brightness,

but not as sophisticated as the Rolleiflex

and more prone to mechanical troubles, especially

the film winding and focusing mechanisms.

If you can get one in nice shape at a good

price, it might be worthwhile, and they

sure look very cool. Prices vary widely

but make sure it has a Tessar 75mm f/3.5

lens and Compur-Rapid or Synchro-Compur

shutter.

Zeiss

Ikoflex Favorit: A well-made classic TLR

with sharp 75mm f/3.5 Zeiss Opton Tessar

lens, bright

viewfinder, and built-in selenium meter,

but the film-wind

mechanism is not as reliable as the ones

in comparable Rolleiflex cameras.

Other

great TLRs worthy of consideration:

The Yashica-Mat with an 80mm f/3.5 Yashinon

or Lumaxar taking lens, not other models

with Yashikor or Yashimar lens; the Minolta

Autocord with a Rokkor 75mm f/3.5 lens,

which is often hailed as the second-best

TLR ever after the Rolleiflex; and the Ricoh

Diacord G, a sleeper with a fine-performing

Rikenon 80mm f/3.5 taking lens and bright

viewing system.

Yashica-Mat:

A great value, this TLR is robust and

reliable, with sharp four-element Yashinon

or—in early models—

Lumaxar lenses. The outer bayonet

accepts Rolleinar close-up lenses.

Late-model 124Gs with

built-in CdS Hexanon meters are more expensive

and they have plastic control dials.

Getting

closer, and steadier

If

you want to shoot portraits similar to the

ones shown here, you’ll want to be able

to focus somewhat closer than the three-foot

or so minimum focusing distance of a typical

non-interchangeable-lens TLR. The best answer

is the Rolleinar close-up lens sets made

by Rollei that click into the outer bayonet

mounts of your TLR’s viewing and taking

lenses. There’s a parallax-compensating

prism built into the unit that mounts over

the viewing lens and it provides surprisingly

accurate framing at close distances. Most

TLRs including older Rolleiflexes, all Rolleicords,

and most other TLRs with f/3.5 lenses use

the Rolleinar 1 mount, and the most useful

one is the R1, which gets you down to about

two feet. If you want to get even closer,

there’s an R2 and R3 set.

Davis

& Sanford Traverse TR-553-228

Since

TLRs don’t feature super-speed lenses

and if you want to get crisp images, it

helps to use a tripod when shooting at shutter

speeds of 1/60-second and slower. Since

the best tripod is the one you take with

you, I always carry my trusty Davis

& Sanford Traverse TR-553-228, which

folds to 12 inches, extends to 53 inches,

weighs only 2.6 pounds, and will support

cameras up to 10 pounds.

Developing

and printing your medium-format film

Unless

you’re a diehard traditionalist, you probably

don't want to set up a complete wet darkroom

and make prints the old-fashioned way. Fortunately,

these days you don't have to; the only part

of the process that still requires darkroom

chemicals is developing the film. You can

bring your 120 film to a local pro lab;

however, those are becoming relatively scarce

outside of the larger cities. An alternative

is to mail your film to labs for processing,

using pre-paid mailers, or to contact labs

directly. When working with labs, you often

have a choice of traditional developers

to use, such as HC-110 or D-76, as well

as the option to have contact sheets, scans,

and prints of your negatives made at the

same time.

Epson

Perfection V800 Photo Scanner

You

can, of course, also scan your own medium-format

negatives at high resolution by opting for

a format-compatible scanner, such as the

Epson

Perfection V800 Photo Scanner

or the Epson

Perfection V850 PRO, which has enhanced

software options and additional film holders,

and then print them out yourself on any

high-quality inkjet photo paper of your

choice. If you’re in the market for a

printer that turns out excellent black-and-white,

I strongly recommend that you get one that

uses pigmented inks and an ink set that

provides at least three gray/black inks

to achieve optimal tonal gradation. Here

are some suggestions: Epson

Stylus Photo R3000 Inkjet Printer, which

has a maximum print size of 13 x 19 inches

and uses a nine-ink set; Epson

Stylus Pro 3880 Inkjet printer, which

increases the maximum print size to 17 x

22 inches and also uses a nine-ink set;

or the Canon

PIXMA PRO-1, which has a 13 x 19 inch

maximum output size

|